A renaissance in urban cycling is forging ahead in many cities, generally, ones that are dense, flat, and that have a wealth of building stock predating the age of basement garaging. But what if the city you live in isn’t like that? What if your city happens to be one of the thousands worldwide that grew late, out, and up (that is, up the face of steep hills)? What if every sign points to your city, remaining a bicycling backwater and deathtrap for the handful who try?

One role I see for myself in the worldwide shift toward bicycle transport (something all cities must do for the sake of the planet) has been to study and find cycling solutions for cities trailing the charge: cities where travel times by car may never be so slow that people turn to bikes just to beat gridlock; cities that will never elect pro-cycling mayors with mandates to take road width from drivers and give it to cyclists; cities where the majority don’t want speed limits lowered.

My role has been imagining scenarios for developing marginal space for a marginalized lifestyle. It won’t be marginalized once buildings and districts have been specially designed for bike transport. When people see the symphony that can exist when the most elegant mode of transport has environments designed to match its dynamics, I expect many will be selling their freestanding homes there in car-land and choosing life in the kinds of apartments I will illustrate at the end of this post.

Unsurprisingly, my bird’s eye perspectives on bike planning often overlap with the street-level perspectives we form while riding our bikes. Quotidianly, we want consideration from drivers, infrastructure like the Dutch and the Danes have, or electric assistance because someone built our houses on top of steep hills. If cycling is to serve any meaningful function in car-focused cities, we need to step back from our immediate impulses and agree on some intelligent strategies. What follows is a 5 step guide. It is more about getting our ducks in a line than solving our immediate worries.

Table of Contents

Step 1: Don’t get fixated on roads.

Recognize that the story you tell yourself about car traffic gradually giving way to bike traffic on your city’s streets is just that: it is a story. The academic term is “metanarrative, “and the academic consensus is that metanarratives are not to be trusted. All you really know is the state of the road at the moment (uninviting to would-be cyclists) and the dominant attitude among voters who think roads exist for them and their cars.

Step 2: See your city as a multi-game court.

The good news is that resigning yourself to the state of the road needn’t mean relinquishing your right to safe and dignified life of bike transport, any more than the popularity of driving stops those who prefer riding on trains from living, working, and shopping along their cities’ main rail routes. Differing lifestyles can coexist. Another is living in an urban village, pursued by people who manage to find shops, schools, and jobs within walking distance of their inner city apartments. A fourth is the life of bike transport.

If we think of each habitual mode choice and attendant preferences for housing and jobs as a game, we can see the city as a field marked for multiple sports. Our cities have already been marked for the three dominant games (driving, riding trains, and walking), but they have to make room for what could take off as their most popular game.

The challenge becomes less daunting once we realize that all of these games use different parts of the field and don’t all use the same goalposts. While the Jeremy Clarksons of this world are shooting for industrial parks and shopping malls in the outfield…

…the Berts and the Ernies have their goals (Hooper’s Store, Oscar’s trash can, the stoop where everyone meets) clustered together in the center of the field…

…while Taras Grescoe and his Straphanger pals have their goals strung along the main train lines that link the corners of the field through the center.

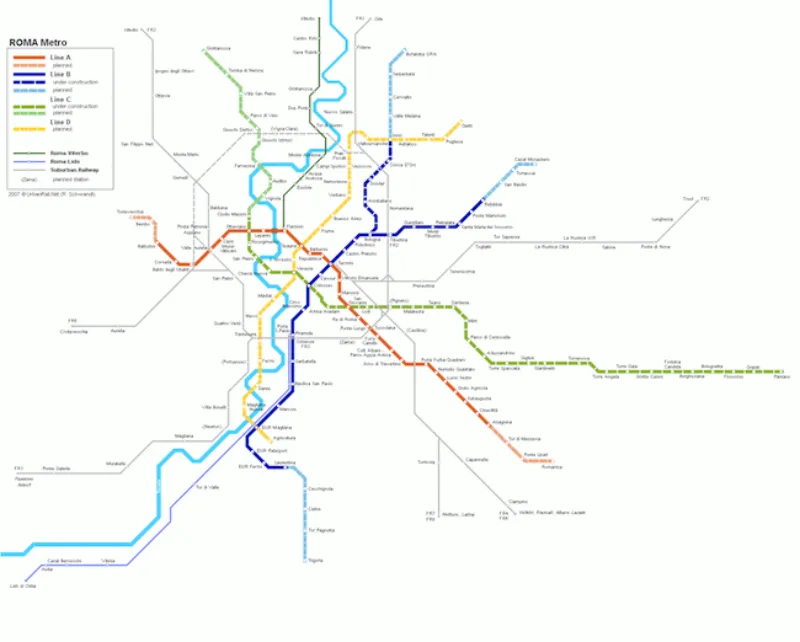

(The three maps above correspond to each of those lifestyles as played on the field known as Rome.)

What is important to note is that when the fourth game is properly introduced, it will have its own set of goals. How do we know where they will be placed on the field? The answer to that comes by imagining how the bike transport lifestyle would be played if it had its own field.

Step 3. Imagine a mono-modal city of cyclists.

If we could design a city from scratch where every citizen used a bike for all trips, we would start with the assumption that it would be flat and have extremities that were no more than half an hour from the center by bike. A 15km diameter circular city would fit the bill.

Such a city should also have a permeable street grid, like Barcelona’s Eixample district, and have many buildings raised on piloti. This is so cyclists could ride as the crow flies. With an earlier blog post, I used maths and some assumptions borrowed from transport geography to ascertain that average commute times for cyclists in a 15km diameter permeable city with no motorized traffic on the ground to obstruct cyclists would be 24 minutes for those who ride at 15kph, or 18 minutes for those who can maintain 20kph—the speed most riders in Copenhagen maintain to stay with the green wave. (The following graphic represents 1000 randomly picked trips in a 15km diameter city. )

We’re not talking about a small village or regional town here. If a 15km diameter city had the same population density per square kilometer as the island of Manhattan, it would have 6 million people. Cities in that population band have average trip times of 30 to 40 minutes, not 18 to 24.

18 to 24-minute average commute times in a city of six million people! Can you see the potential? We want to bring this fourth game to the city’s multi-game field will not only be played by those who care for their health or the planet’s health. Workers will play it, employers, couriers, merchants, and service providers; in fact, anyone is drawn to the city by the opportunities provided to quickly access the large markets they promise.

Step 4. Find room for your game among all the others.

Most car-centric cities have centrally located flat lands to spare. During the age of the car, and before that, the street car, it was easier to unlock hills for development than low-lying planes. The only public infrastructure needed to build on a hill is a road or a tram line that can be extended as needed. Before low lands can be developed with high-value functions like housing, entire levee banks need to be built. Flat lands became the sites of our factories, docklands, and goods yards even near a town. Interestingly, many such facilities have been abandoned as our cities have entered their post-industrial phases.

It serves two agendas (urban consolidation and urban cycling) to map all this land and ways non-vehicular easements like waterways or former rail routes might link them all up. The following maps show the extent of the underutilized flat lands within 15km diameter circles of interest in some of the cities we have looked at this way.

Some of the districts we have colored in blue are bigger than whole cities in the Netherlands. Not all can be covered in apartments and public buildings targetting those of us pursuing “game four.” Enough of them can be thought for us to see at a glance that room exists in the fields of our cities for a lifestyle-oriented around the overlooked mode.

Step 5. Design the right goalposts.

Whether it’s an end zone, goal post, finishing line, a ring on a pole, or a hole in the ground, every game has a goal to suit. The same is true for lifestyles that give preference to particular modes. Freestanding buildings dwarfed by their own car parking lots are the usual goals for those habituated to driving. Tall buildings clustered around stations are the straphangers’ goals. For people who idealize a lifestyle of short walking trips, it is common to have goals that involve walking up stairs, given their propensity for old recycled buildings.

In those parts of the field where we see merit in pursuing the bike transport game, the goals should be designed to suit the secret desire of every person who enjoys cycling: to bring their bike with them inside.

There is not a lot in that post that I haven’t published in blog posts or magazines or indeed said in my talks. What is new is the sports field analogy. The hardest thing about loosening fixed minds is finding just the right words. Few strategies are as effective as a perfect analogy. I would be pleased if this particular post got some shares.