My box bike (or bakfiets in Dutch) can go where no pedestrian or vehicle can go. It could traverse slopes that would hurt peoples’ ankles if they walked. It can fit through gaps that vehicles are unable to fit through. It is safe enough and clean enough to be ridden indoors. And it can shrink spaces that anyone in a hurry would find too vast and boring for walking. All this means a unique kind of city can generally be built around box bikes and bicycles.

Wonderful building types and urban patterns have been conceived that capture the essence of virtually every mode by which humans can move. Walking-inspired porticoes, ambulatories—virtually everything. Boating didn’t just give us passenger terminals, but Venice, Gilpin’s key text on the Picturesque, and the twentieth-century genre of the shipbuilding.

Flying has given us airports and Eero Saarinen. (I adore the image above of Pereira and Luckman’s original vision for LAX airport). Train travel gave us George Gilbert Scott’s St. Pancras Station and is mentioned throughout Ebenezer Howard’s book Garden Cities of Tomorrow. And driving inspired nearly every new building type of the twentieth century.

The poor old bicycle has really been left out of this history. How many buildings try to capture the essence of two-wheeled human-powered movement? The velodrome? The Danish Pavilion at the Shanghai Expo in 2010? There really aren’t many.

It’s nice that Houten and Milton Keynes had bike routes planned from the start, but that hardly makes these examples of bicycle urbanism. Both cases’ more serious design constraints stemmed from the decision to provide car access.

It’s also nice that an architectural idiom has appeared in new Dutch and Danish architecture: the giant awning protecting parked bikes near the door. But I think we can do much more, as cool as that is!

I want architects and urban designers to take their minds back to when they were children and the day they realized their mum or their dad was no longer holding the seat of their bike. I want them to imagine that the street or the park where they first rode a bike is like plasticine in their hands, and they’re going to mold the world according to this feeling that we all can remember, that we have just learned to fly.

I would like to propose 5 defining characteristics of built space that speak to this feeling of flying:

- 1. the ground plane is leaning and contoured in ways that might hurt your ankles if you were walking but which feel wonderful under your tires. You find very few people walking in front of you on this surface.

- 2. related to point 1, the undulations help you speed up and slow down without braking or pedaling harder,

- 3. the space you are in is quarantined from motorized vehicles;

- 4. you can find shelter if you need to get out of the sun or the rain, and

- 5. everything is further apart than if it were designed for the speed of the walker, but not so far apart as things are in districts that are designed for car drivers.

If you’re an empiricist, who needs to relate every new thought to something you have experienced with your senses, you might struggle to follow all this. “Where are these 5 characteristics in Holland?” you ask. You’ve got to understand that I’m being Rationalistic in the way I am thinking. Rationalists throughout history, like Descartes and Plato, have maintained that observable models can be a barrier to us using pure reason. From a Rationalistic standpoint, one’s eyes should not be so seduced by what they see in Amsterdam or Copenhagen that their mind can’t freely imagine a district built especially for cycling. You may need reminding that old cities were built for walking and horses. The bicycles came along later.

Why do we need to imagine a purpose-built bicycling city? It’s not so we can bulldoze old city centers. It’s so we can stop the proliferation of brand new urban districts with race track curbs and basement car parking. These aren’t only being built in developing countries like China and India. Most disappointingly, even Copenhagen has done it! The new district of Orestad, a 15-minute cycle from the center of town, is being built over enormous garages and has roads designed to go fast on.

Like brownfield redevelopment districts in all post-industrial cities, Orestad began life with a masterplan promising walkable streets with fine-grain permeable edges—a modern reinterpretation of an old European town. I’ve heard a lot of dilettante “urbanists” speaking as though architects need educating in the ways of that model. If only they knew how my generation of architects was raised on that model. During the 70s and 80s, you couldn’t open a professional or scholarly journal of architecture or urban design and not find at least 2 articles pouring over some aspect of the old European town. And this was all done so that the European town might be replicated on brownfields. It was even said (here) that the old European town replaced the machine as the architect’s main inspiration.

So why aren’t places like Orestad being developed according to the theories architects slaved over during those decades? Well, by the time investor confidence peaked in the early 2000s, developers and financiers weren’t interested in boutique in-fill apartment buildings—the basic type which gives historic districts their character.

They wanted to do block-buster developments because with size come economies. The cost of lifts, rubbish removal systems, sub-stations, landscaping, prototyping, and the latest energy-saving techniques, are proportionally cheaper when you build hundreds of apartments, not dozens.

These are all plusses to large-scale construction, not only for developers but for apartment buyers as well. However, there is one undeniable minus. The greater the sums of money invested, the more conservative investors become. They have all resorted to a retrograde vision of the good life, predicated on lots of car parking and roads designed to go fast on.

Thankfully, that vision is only man-made. It blasted onto the scene with the Futurama exhibition at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York and was rapidly built in the US after WW2 using a huge one-time surplus their government was anxious to spend. It looked like progress, so it was copied all over the world. Nevertheless, it is only new. We see how the vision can be unpicked in city centers with street layouts predating the car.

The next frontiers are the urban districts that haven’t been built yet. These are in developing countries and on our own redundant industrial lands. Can we stop these being planned around cars? I see my work imparting a vision for urban expansion to rival the one we inherited from the thirties.

The hardest part is convincing people that there is no hidden force in nature or heaven, causing car-dependent cities to self-replicate. Henri Lefebvre gave us a beautiful term, “the production of space, ” reminding us that cities are artifacts. They’re like the map and the rules of a video game that somebody made. Every new land subdivision, with streets designed to move cars between buildings, is a mistake that culture has made. Aren’t you glad it’s just us and not nature or god? We have the power to change this.

The 1939 Futurama exhibition obviously had some masterful tricks of persuasion to make the whole world suddenly think they could shift to a car-based model of urbanism. So what were its tricks, and can they be deployed to inspire the next radical shift in our culture? The trick that stands out to me, was the way Futurama pushed all the right buttons with mothers.

A passage in E.L. Doctorow’s memoir World’s Fair shows the father coming away from the Futurama exhibition feeling skeptical about taxpayers’ money being used to build roads for GM. It was his mother who Doctorow recalls whispering—so her husband would not overhear—that the Futurama had made her wish for a car.

General Motors sold the car-focused city the same way they sold their cars. They addressed men, fully aware that women are behind most major household decisions.

I suggest we take that tip and design bike-focused architecture and urbanism that promises a more convenient life for a mother than a car city can give her. Let’s begin with a classic scenario: the baby is due for a sleep, mum wants a brisk walk in the park because she’d paranoid about getting fat, and the pantry is empty.

In a car-focused city, she can try to put her baby to sleep in a capsule and transfer that capsule between her car, shopping trolley, and jogging pram. While hardly a joy, the production of space for the past 60 years does everything to clear a path for her, not only with traffic engineering and car parks near all the jogging tracks but with architecture that keeps her out of the rain.

Can we design her a city with even greater amenities? If you nodded off earlier, I’d remind you that I’m concerned with designing a model to rival the only one currently used to build new urban districts. I’m trying to imagine a bicycle-focused model of building new cities to replace the car-focused model that will otherwise continue unchallenged.

I wouldn’t be writing if I wasn’t confident that we could do better. I think the most convenient cities of the future for mothers will be the ones that capitalize on the possibility of using bikes inside buildings. If a box bike had retractable casters, it could be used as a grocery trolley inside supermarkets.

And if the circulation inside apartment buildings was designed around cargo bikes, a mother could unpack her groceries directly into her pantry.

And if the space between her apartment and supermarket was quarantined from motorized vehicles and designed with the kinds of undulations I asked you to imagine yourself molding from plasticine if you were a kid, she could get her exercise and have fun on her way home with the shopping. Don’t worry about the baby getting plenty of sleep. If you have ever laid one down in a box bike, you will know these things are like a double dose of Phenergan!

Supermarkets and malls are already perfect for riding inside. All we have to do is convince retailers that bikes are not horses and aren’t going to poo on the floor if they let them inside.

The apartment building is the greater architectural challenge. At the moment, it makes leaving home on your bike about as natural as washing your hands after the toilet, before the advent of basins in houses.

Last century building design changed to incentivize hand washing. That event greatly reduced infectious diseases. This century it would be nice to see building design change to incentivize cycling, to reduce chronic disease.

There’s a building type I would go so far as to claim as an “invention,” the “slip-block,” that I think would make leaving home on your bike as natural as washing your hands after the toilet. It’s just like a slab block. Only the access corridors on every level are gently sloping. Coming home tired most people would choose to take the lifts. These go to the high ends of their sloping access corridor so they can roll down to their apartments—wherever those happen to be along the length of their corridors. When they leave their apartment, it’s easier to ride down the ramped corridor that eventually brings them down to the ground than it is to ride back up to the lift.

Since the lifts get half as much use and also serve a lot more apartments, the lifts can be doubled up, and each is made big enough for 5 or 10 bikes.

And to save cyclists from braking on their way down, kinetic energy harvesting tiles can be used to help power the building.

Now I’ll admit, the worst case scenario—the uppermost floors—could have some very long access corridors to descend.

And because of that, I know naysayers will draw pejorative associations with aerial streets in Northern England or St Louis. They forget government policies, not aerial streets, made these into ghettos. My background is as a public housing architect in Singapore, where we did long aerial streets that all worked perfectly fine. The trick is to make an aerial street a defensible and neighborly place with fresh air and daylight. One way is by punching holes from the side or the top.

Another is to put eyes on the aerial street with fire-rated windows looking out from apartments.

Residents will also care more about the goings-on in a corridor where they have been allowed to park a few bikes. I’m actually imagining parked bikes creating a barrier to protect people walking from people on bikes.

I met a developer in Boston who insisted there isn’t room for bikes in apartments. He doesn’t understand that his apartments are tiny because his permissible development envelope is being chewed up with car parking pods.

The next question is, how can slip blocks be arranged on a site? A good design method is to align all your blocks to maximize sunlight and views, then introduce something like a piazza or avenue to add legibility. So here’s the ultra-rational starting proposition laid over a vacant site in Orestad in Copenhagen.

It’s actually not as bad as it looks. The Avenues are as wide as Park Avenue in New York. The wedge shapes also mean many apartments have angled views over part of the roof of the opposite block.

Nevertheless, a gateway and a hierarchy of places would make it more legible as a few of my students showed with this variation:

Other students have been looking at a similar-sized site in Singapore, on the docks at the end of an old railway that is now being turned into a greenway—the perfect site for a bicycle-oriented development in a country like Singapore, where the roads are treated as a tax revenue source.

No one cares about overshadowing the equator. Here you want to minimize east and west-facing walls and give apartments a view. Three students looking at this site recently came up with the idea of giant zig-zagging slip blocks in a bid to reach Singapore’s extraordinary density targets while maximizing the number of units with views and, of course, giving everyone that encouragement to leave home on their bikes that you would get from a slip-block.

I’ve shown you the slip block and ways it can be flexed. If you like now, you can imagine the ground floor packed with cafes and owner-operated fruit shops creating a fine grain permeable edge. Throw in some yarn bombing, and you have the urban designer’s pat answer.

The problem with that answer is not many people remember the question. A quick history lesson for you: the discipline of Urban Design started with a conference at Harvard in 1956 aimed at building chance interaction back into cities and designing defensible space. Since social isolation was attributed to freestanding towers and cars, they naturally saw low-in-fill buildings and walking as the solution.

There are some problems with walking, though. It doesn’t increase your metabolism like cycling, so it has been found to make populations gain weight if that’s all they do. It doesn’t meet the commuting requirements of households with specialized jobs, schools, and hobbies. And because it’s so slow, it only lends passive surveillance to a handful of streets, the ones where shops gather tightly to catch pedestrian trade—most streets have no eyes upon them.

The logical answer to the problem of chance interaction and passive surveillance is not a cafe strip in a city where everyone leaves their apartment riding a bike. The opportunity exists to scatter shops evenly across the whole city or district. Since the slip blocks have ramps reaching the ground every 60meters, these can be treated as activity nodes, with entries to apartments and shops. By raising these nodes, you can help cyclists slow down without braking.

If high means slow, then low means go: in other words, channels can be used as bicycle expressways leading to whatever linear routes might connect bicycling districts across a post-industrial city.

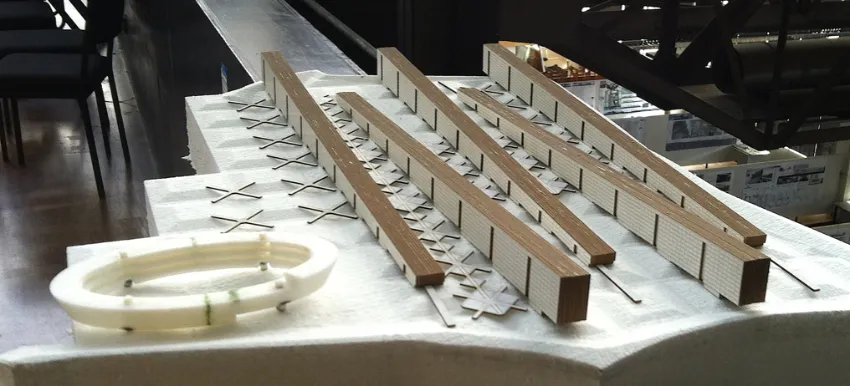

Pictured above is a 2.2-meter deep channel with a 14% grade rising to activity nodes and flyover bridges for pedestrians and slower cyclists.

Flyover structures can be extended to provide rain cover and shade to cyclists below. This last image shows a proposal employing these principles on Singapore above site. Without going into the fine grain detail that would break down the scale of the ground plane, the drawing conveys a basic conceptual strategy of placing building entries and shops on crests and linking these with pedestrian bridges. The lower level, represented by blue, lets cyclists follow their own desired lines on a field singularly designed to capture that feeling of flying we all remember from when we were kids.

I’m taking these ideas to the Netherlands next week. This post is an essay I’ve written to gather my thoughts ahead of those talks. So if you’re planning on coming to Nijmegen on the weekend or coming to the bike night in Amsterdam, you’ve just been given a chance to ask questions in advance. I would certainly appreciate any feedback, and I truly thank you for having just read a 3000-word blog post! Thanks, too, to the many Masters of Architecture students at the University of Tasmania who have worked with me to refine these ideas! I’ll happily put them in touch with any clients or employers looking for talent!